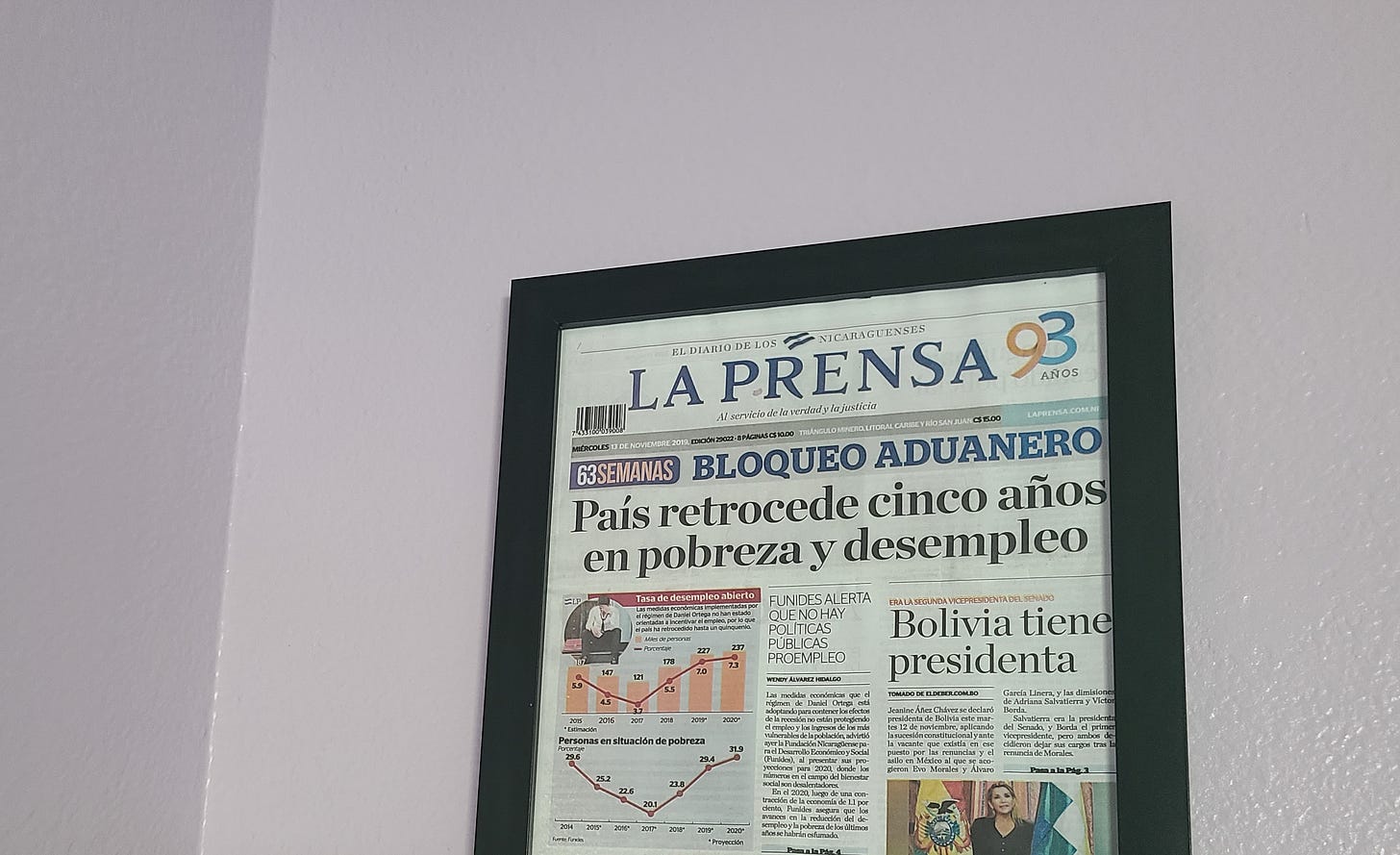

Above my desk, I keep a framed copy of the Nicaraguan newspaper La Prensa from November 2019.

At the top, the paper has a banner that counts 63 weeks — the then-tally for how long the Nicaraguan government had kept La Prensa's printing paper blocked in customs as a means to silence dissent and criticism.

I've met many Nicaraguan dissenters — human rights workers, journalists and small business owners among them — seeking asylum at the San Diego-Tijuana border, where I've covered immigration news since 2016.

The framed newspaper reminds me of the kind of persecution that people are often fleeing when they show up at the line that separates the United States from Mexico. It also reminds me of the privilege that I have to do this job in a country whose founding documents protect journalistic freedom so absolutely.

Now that we are facing a second term from a president who has called journalists “the enemy of the people,” I am leaning into another of the newspaper's reminders — inspiration to do my job as fiercely, diligently and thoroughly as I possibly can.

The day after the election, I thought about how much work went into covering the rapid-fire immigration policy changes that happened under President Donald Trump the first time around — and how much journalists will need to do in the coming years.

I asked myself what I can offer in this moment. The result is this newsletter.

Beyond the Border will help you keep track of changes in the immigration system and, most importantly, show you the ways that those changes affect people. It will include original reporting from me and highlight the work of journalists around the country.

Based on his first term, we can expect that a second administration from President Donald Trump will involve a whirlwind of policy changes. In his first week in office in 2017, he signed three executive orders related to immigration that mapped out the ways his administration intended to restrict access to U.S. soil and deport people who were already here.

I spent most of the next four years witnessing and documenting what those executive orders meant in practice.

In 2017, I visited a Syrian refugee family during Ramadan to learn about how the parents and daughters became separated from the family's only son as they fled for their lives, and how U.S. policy made it nearly impossible for them to reunite. I went to an immigration detention facility to meet several fathers who were among the first family separation cases months before the program was formally announced.

In 2018, I spent time with the traumatized girlfriend of an undocumented college student who had been taken by Border Patrol from her car and later visited the student himself in the detention center. That year, I also followed the cases of asylum seekers who arrived at the border in migrant caravans, and I documented the U.S. government's surveillance of the people who provided humanitarian aid to the migrants.

In 2019, I waited for days and weeks at a time in a plaza on the south side of the San Ysidro Port of Entry to learn about the ways that U.S. and Mexican officials were working together to keep asylum seekers from reaching U.S. soil. That plaza was also where I waited to meet asylum seekers returned to Tijuana through the Remain in Mexico program.

And, in 2020, I stayed ready by my phone for people held in immigration custody to call. They told me about the lack of COVID-19 protections there. I also mourned with community members about the loss of loved ones during the pandemic and the way the border affected their ability to grieve.

I cannot predict with certainty what the changes over the next four years will look like. What I do know is that I intend to do my part as a journalist to help you stay informed through reporting that is accurate and fair and human.

For many people living in this country, the border is an abstract and scary term batted around by pundits, politicians and even journalists who haven't spent significant time here. But for those of us who live near it, the border is a line on the ground across which people live their lives.

Beyond the Border means focusing on those real, human lives, not the mythical chaos that the line has become in rhetoric.

This newsletter will begin a regular publication schedule in early January. You can subscribe for free or for the equivalent of buying me a hot cup of decaf Earl Gray once a month. (I am, unfortunately, very sensitive to caffeine.)

If you're eager to find ways to support this journalistic mission, I have also launched a GoFundMe to help me get a crucial tool — an old truck or SUV — to do this work as fully and safely as possible.

In the meantime, you can find me on Instagram, Bluesky, Threads and (testing it out) TikTok.

(If you are one of the journalists whose work should be featured in this newsletter going forward, please send me links so I can follow you in places other than the wasteland that was once Twitter.)

Take care and stay well.

P.S. If you want to know a little more about me:

I was at The San Diego Union-Tribune until July 2023 when a new owner bought the paper. (You can read what happened here if you're interested in the industry tea.)

While I was there, I wrote a four-part series on the U.S. asylum system called “Returned” that looked at the ways the system fails to protect the people it was intended to help and what could be done to change it. That project won the Overseas Press Club Robert Spiers Benjamin Award for best reporting in any medium on Latin America.

I've spent the past year working on a book and doing the legwork to co-found a new local news outlet for San Diego. I've been teaching journalism at two colleges and freelancing for Capital & Main and Voice of San Diego.