Special edition: What we've seen so far from Trump's executive orders

A plaza in Tijuana is once again the place where asylum seekers wait — confused, despairing, yet hopeful for change

Hello dear readers,

Initially, I intended to publish on the second and fourth Tuesday of the month, but so much has already happened this week following President Donald Trump's inauguration and subsequent executive orders that I felt like I owed you an extra edition. I hope I'm not taking up too much space in your inbox. As always, I'm open to feedback.

Let's get into it.

When the United States suddenly changes its border policies, El Chaparral, a plaza at the southern end of an official walkway between San Diego and Tijuana, has for years been the place where migrants wait to find out what is coming next for them.

It's where deportees have returned to Mexican soil, re-laced their shoes and called for someone to pick them up. It's where asylum seekers gathered to hear their numbers called every morning from a notebook that tracked the unofficial, yet official queue to enter the United States from 2018 to 2020. It's where a group pitched tents while waiting for former President Joe Biden to restart the asylum system early in his term.

And on Tuesday, it was where you could see the most immediately visible impact of the stack of executive orders that Trump signed on his first day in office.

Dozens of people who had appointments scheduled through the phone app CBP One stood by the gate to a parking lot where previously the line of those who had won the scheduling lottery followed Mexican officials into the port of entry several times a day. The app, created under the Biden administration, had become the only way to request asylum after the former president made a rule barring people who entered through other means from being granted that form of protection.

On Monday, Customs and Border Protection canceled all future appointments. Only those who arrived for the earliest time slots made it in on Inauguration Day.

CBP deferred to the White House when asked about the change. The White House did not respond to a request for comment. An executive order that Trump signed included the change in its long list of border directives.

Among those suddenly stranded in Tijuana on Monday were two comadres, or close friends, from Colombia. The two women said each had faced death threats in their home country around the same time. They'd decided to flee together to the United States, where another close friend offered to help them.

They said the “wings of God” helped them get through immigration checkpoints as they moved through the hemisphere mostly by plane, a difficult feat given the United States’ pressures on other countries to stop migrants from reaching its borders.

(The two women and other asylum seekers in this newsletter asked not to be fully identified because of ongoing dangers.)

The comadres arrived in Tijuana on Sunday after waiting further south in Mexico to get an appointment. Then, the app suddenly rescheduled their appointment for February, they said. They went to the port of entry to ask an official for help. The official was also confused, they said.

Then, they found out that their appointment had been canceled.

“One understands he wants to get the house in order, and we want to arrive to a country in order,” one of the women said in Spanish, referring to Trump. She said her family members who live in Georgia support the current president.

“But we tried to do things the right way, and we're stuck here,” the other added.

They said that a woman they know who was still waiting for a CBP One appointment in Tuxtla, Mexico, tried to apply to stay in Mexico after the news came out on Monday. Mexican immigration officials told the woman that she'd been in the country too long to qualify, they said.

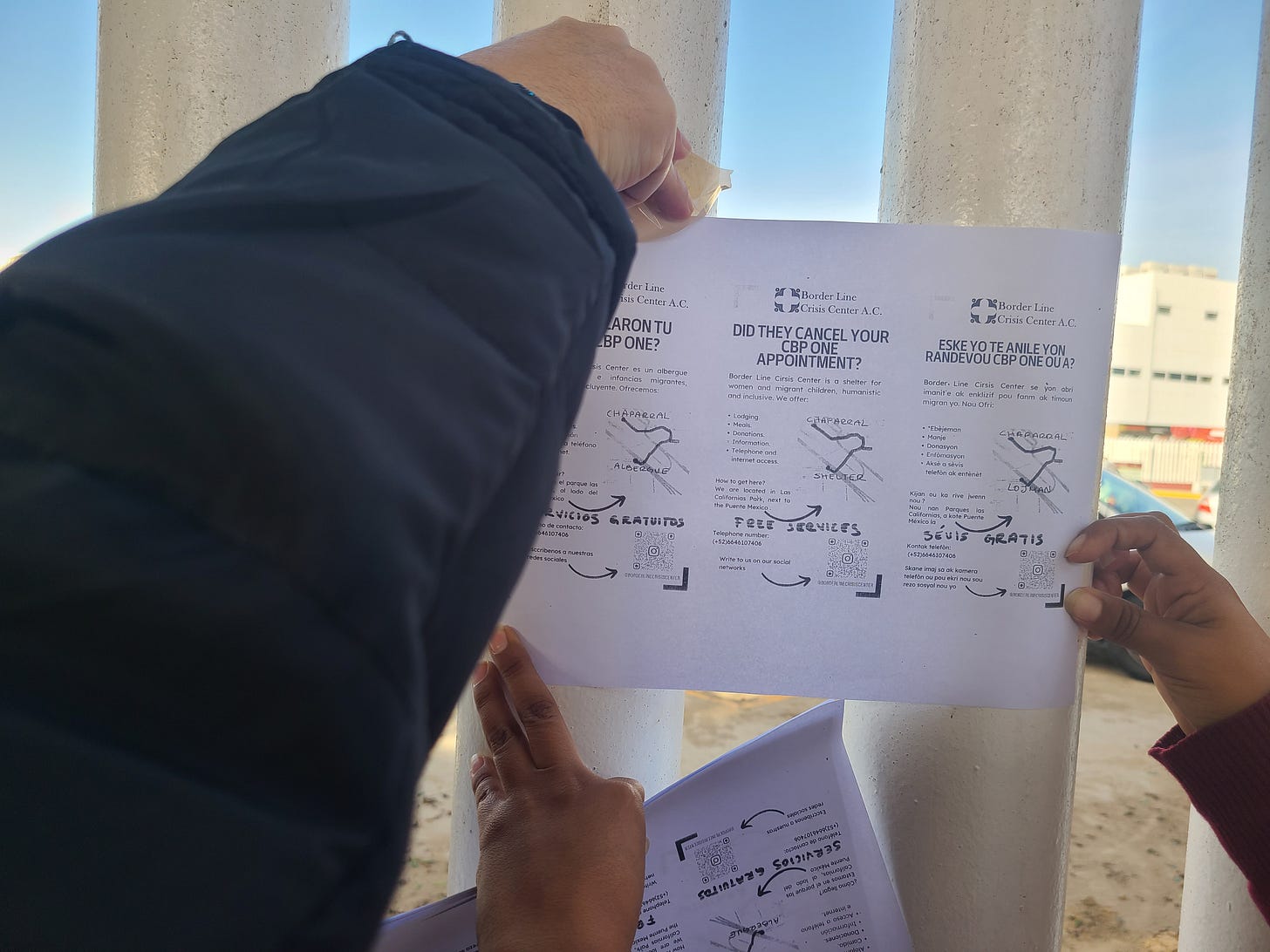

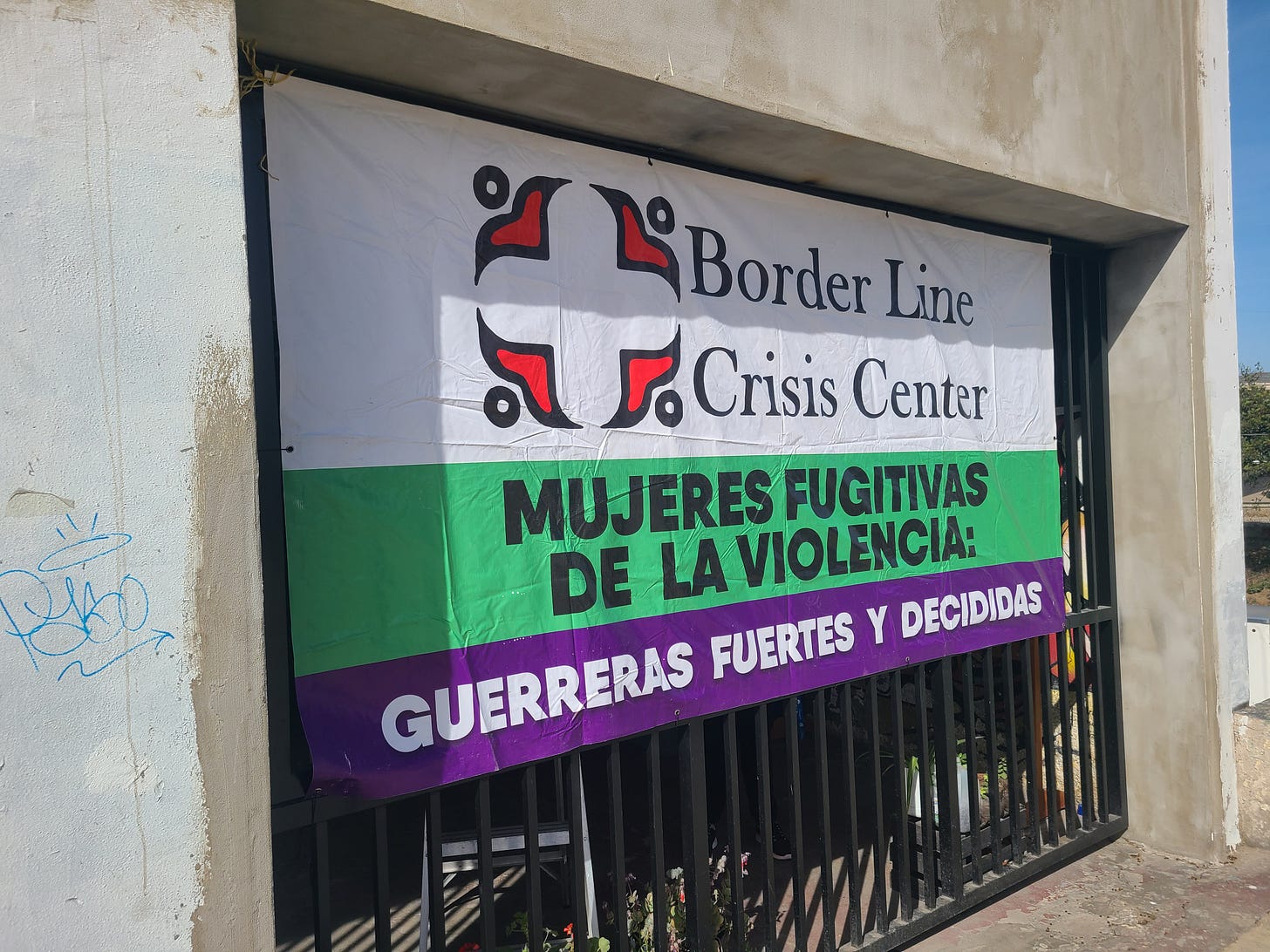

The comadres stayed in a Tijuana hotel paid for by a friend Monday night and went to Border Line Crisis Center, a shelter that takes in women and children, on Tuesday morning. Within a couple of hours of their arrival, they were already helping Judith Cabrera, who runs the shelter, pass out flyers and hang signs at El Chaparral. They counseled other asylum seekers to find shelters like they had so that they could wait to see what comes next.

In a preexisting lawsuit challenging the Biden administration rule that barred asylum to people who didn't enter using the app, attorneys have already challenged the end of the CBP One appointments.

Meanwhile, at Border Line, several families with canceled appointments were devastated that they no longer have a way to ask for help.

A woman from Guerrerro, Mexico, said that she had fled with her two young children from a violent partner after her sister's partner killed her sister without any repercussions. She was terrified the same thing would happen to her if she stayed in Mexico.

“I ask that they give us the opportunity to be there because there are women who need to be there, and when there's no opportunity, we have no choice but to – sometimes we have to die,” she said softly in Spanish, tears on her face. “I think many women will not survive.”

Isabel, a grandmother from Honduras traveling with her three grandchildren and hoping to reunite with her daughter in Miami, also had an upcoming appointment until CBP canceled it Monday.

“It feels like someone threw cold water on you,” she said in Spanish.

All of the women were hopeful that the administration's promised reintroduction of the “Remain in Mexico” program would at least give them a pathway to requesting protection since there isn't currently one at the border.

Remain in Mexico, known officially as Migrant Protection Protocols or MPP, started at the San Diego-Tijuana border in early 2019 and required asylum seekers to wait south of the border while their immigration court cases proceeded in the U.S. People waiting in the program frequently experienced violence — including kidnapping, extortion, assault, rape and murder — at the hands of cartels and other criminal groups in Mexico.

Ray Rodriguez, a former professor from Cuba who was one of the few granted asylum while waiting in Matamoros in the Remain in Mexico program, said on a press call Wednesday that it's painful for him to hear that it's coming back.

“It's a horrible situation to be in,” he said. “You come here to ask for asylum, to ask for refuge and you're sent back to these conditions… The things that you go through while you do that — I had to learn how to live with the sound of gunshots all the time.

“There's no protection at all,” he added. “I thought we had learned from the fact that it was inhumane to the core, the program.”

It's not yet clear who will be placed in the Remain in Mexico program this time around or how someone would even access it. An official not authorized to speak publicly said that the details are still being negotiated between the U.S. and Mexico.

Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum suggested yesterday that Mexico would “repatriate” people placed in the program to their home countries.

“What will Mexico do? We'll act humanely, but we also have our migration policy,” she said, according to an English transcript of her remarks.

In Wednesday's morning briefing, Sheinbaum told reporters that federal shelters were ready to receive migrants with canceled CBP One appointments. She said those migrants would only be sent to their home countries or other Central American countries if they went voluntarily.

Some parts of Trump's executive orders seem to try to cut migrant access to U.S. soil completely, and an asylum seeker has to reach U.S. soil to ask for protection, even to get into Remain in Mexico. Other parts of the orders suggest that people might be sent back without any documentation or court case, more in the style of expulsions used during the pandemic under another policy called Title 42.

“It's not clear how all of these different executive actions fit together,” said Melissa Crow, director of litigation for the Center for Gender & Refugee Studies. “I feel like it's almost like a pinball machine where you try to hit as many balls as you can in the hope that you're going to ring the bell. I think [Trump officials] are trying to give themselves as much latitude as possible.”

Robyn Barnard, senior director of refugee advocacy for Human Rights First, said that some reports have already surfaced that people are being expelled at the border. I asked Mexican immigration officials about both expulsions and Remain in Mexico, and the agency has not yet responded.

That's all for this week. I intend to be back for our regularly scheduled program on Tuesday with a better round up of other reporters’ work and any updates I can wrangle myself. In the meantime, if you have questions or if you see anything that you think deserves to be highlighted, please send them my way.

Take care and stay well.

I can vouch for Border Line Crisis Center, if anyone is inclined to lend some support.